How does high pathogenicity evolve in avian influenzas?

Here's my hypothesis, for what it's worth....

In its simplest terms, evolution works by two processes. First, mutation and reassortment provide genetic variation. Second, selection favours the sets of genetic material that are most fit (i.e., will leave more progeny than other sets of genetic material). These processes work with all living things, whether they are influenza viruses or humans.

With respect to influenzas, wild birds of various species are the reservoir for all avian influenzas. However, these viruses tend to be of low pathogenicity (LPAI), causing only mild transient illnesses. Until this year, science had described only one outbreak of a high pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) in wild birds in the absence of affected poultry populations - an outbreak of HPAI in common terns in South Africa in the 1960s. Since its emergence in 1996, H5N1 had been isolated from a few wild birds that clearly obtained the virus from nearby infected domestic bird populations. However, these were local spill-over events, and the virus was not sustained.

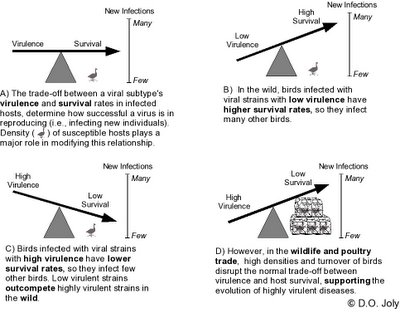

So how do you get HPAI in poultry from LPAI in wild birds. My hypothesis, and I don't claim that this is original, when HPAI strains appear through mutation and/or reassortment, the conditions do not favour the HPAI strains over endemic LPAI strains (see figure below). In contrast, in the wildlife and poultry trade, the high turnover of susceptibles, poor sanitary conditions, and high stress fuel the fire, so to speak, and HPAI strains become dominant through natural selection. This is why HPAI H5N1 first appeared in the markets of southern China.

However, something has changed this year. HPAI H5N1 seems to be persisting in wild bird populations, at least long enough to get to Mongolia and perhaps to Eastern Europe. Now this is totally speculation, but perhaps the evolutionary landscape for influenza is such that HPAI is unlikely to evolve in wild birds, but now that it has evolved in poultry and domestic waterfowl, it is capable of persisting in wild birds. It remains to be seen how long it will persist.

8 Comments:

Thanks for the explanation. I can certainly understand why the high turnover of susceptibles would favor high path. Not so sure about the mechanism of the other two.

Okay have figured out high density. But what about stress?

I would guess (and this is only a guess!) that the highly stressful conditions would create immunocompromised individuals (and consequently increase viral shedding), and poor sanitary conditions would facilitate disease transmission. You are correct - although these conditions might not facilitate evolution of pathogenicity, they would increase opportunity for disease transmission.

I'm an ex-HIV epidemiologist, but more on the statistical side than on the biological side. Maybe, maybe not re: stress.

Can you explain the pathogenicity importance of changes at the H5 cleavage site? I am still trying to understand that.

Do chickens etc get stress diarrhea?

Can you explain the pathogenicity importance of changes at the H5 cleavage site? I am still trying to understand that.

Nope - sorry! I'm a more of a data geek myself (see link to pubs at top right).

Ah, two geeks together. I certainly appreciate your blog. Very informative. I retired two years ago and sure do miss my easy access to journals through the state health department I worked for. Too expensive for a retired state worker.

I find Google Scholar to be a pretty good resource for getting access to articles - often if it can't a PDF of the real version, you can get preprints etc.

Post a Comment

<< Home